"Death Reflects Life"

A Self-Guided Walking Tour of the Cemeteries

Welcome to the historic Mount Zion and Female Union Band Society burial grounds

The Mount Zion Cemetery (encompassing the earlier Methodist congregation burying ground) and the Female Union Band Society Cemetery are two of the oldest Black Ancestry cemeteries in Washington, DC. They are a physical reminder of the heritage, contributions, and sacrifices made by enslaved Africans, their enslaved descendants, and free Black people during their lifetimes. They also provide insight into their families and the community in which they lived during a time of deep segregation.

Together, they are the only two cemeteries remaining in the District which were specifically maintained for the burial of enslaved and former enslaved persons. They are among the few Black history landmarks remaining in Georgetown, a community whose population during the late nineteenth century was between 35 and 45 percent persons of African ancestry.

We acknowledge that before the Methodist Burying Grounds, Mount Zion Cemetery, Female Union Band Society Cemetery, or any of today's Georgetown existed, the land was the ancestral home of the Patawomeck and Nacotchtank people.

The Nacotchtank (this name Latinized by Jesuit missionaries to "Anacostan") are an unaffiliated people that lived within the land of the greater Piscataway tribe for over 2,000 years. They were the inhabitants of Tahoga - a village documented in 1631 by English sailing Captain and explorer James Fleet as located where Rock Creek joins the Potomac River.

These burial grounds are a memorial park - serving as a place to promote unity, appreciation, and to educate. This tour will introduce you to our two cemeteries and acquaint you with some of the individuals for whom this sanctuary is their final resting place. The walking tour takes about 30 minutes to complete - you are welcome to stay for as long as you choose to reflect and continue to learn about this special place. We encourage you to share feedback about your visit using the form at the end of the guide. We hope your visit creates new personal awareness, and a thirst to continue your education.

This guide offers underscored bold font links to additional information about cemetery history, persons buried here, and the vibrant Georgetown community in which these individuals and their families lived and worked.

The cemeteries are private property sanctuaries. Please understand and respect that thousands of burial sites exist throughout the open, wooded, and hillside areas of the memorial park, and most are not defined by a headstone or other marker. The memorials and artifacts that exist are fragile - do not walk on memorials or make 'rubbings' of stone engravings. Dogs are not permitted in the sacred grounds.

The tour begins at the Cemeteries' National Register of Historic Places plaque located at the junction of 27th Street and Mill Road NW

The two cemeteries are adjacent but separate properties comprising roughly equal-sized halves of the approximately three-acre grounds. The park-like open spaces, wooded hillsides, and monuments areas are the final resting place for literally thousands of people who lived and worked in Georgetown, and later, greater Washington, DC, from the 1700s to 1950. Though the cemeteries have unique histories, they are connected through the intertwined lives and community of the enslaved, freed, and free Black persons, early white European settlers, and their respective descendants who are buried here.

'Black Georgetown' was not only a source of skilled craftsmen and laborers for creating the grounds and many structures of Washington we see today, it was a fully formed community of its own. The more than 100 occupations held by Black citizens described in the 1874 edition of Boyd’s Georgetown Business Directory, and confirmed by annotations in Mount Zion Methodist Church member death records, reveal extensive participation in the daily life of the Georgetown community.

The Female Union Band Society (FUBS) Cemetery lies before you - its open plateau, the hillside beyond down to Rock Creek, and the sloped grounds to the left (bordering the unimproved old Lyons' Mill Road public path) are all burial grounds.

Mount Zion Cemetery, the location of the Old Methodist Burying Ground (the oldest burying ground in the two cemeteries), adjoins the FUBS Cemetery and is defined by the several groupings of headstones and memorials seen on the rise directly to your right.

What is the "Female Union Band Society"? In 1842, a group of formerly enslaved Black women, led by Mary Turner, originally from St. Mary's County, Maryland, founded the Female Union Band Society. The Society's constitution, dated 1859, defines the Society as a cooperative benevolent association of free Black women whose members were pledged to assist one another in sickness and in death. In exchange for membership and payment of dues, the organization provided a member $2 per week when she was ill, and a grave and $20 for burial expenses upon death. The document proscribed that membership was restricted to women of "good moral character" who were "recommended by two members of the society." Provisions existed to expel any member "convicted of immoral or disgraceful practices," as well as those who did not pay their dues or who were "disagreeable to a majority of the Society, either by words or actions."

The Society acquired this property to fulfill its commitment to providing graves for its members. As Black women were not legally permitted to own property at this time, the land was purchased from Joseph Ellis Whithall by Joseph Mason, in trust for the Society, for $250 on October 19, 1842, with the deed recorded on August 8, 1843.

Proceed across the burial ground toward the prominent Logan, Ferguson, and Cartwright families' memorials and gravestones

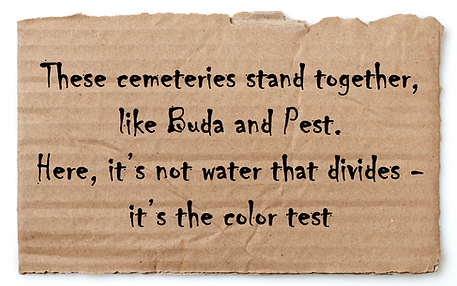

Anonymous poem found inscribed on a placard nailed to a tree near the Lyons Mill dirt road dividing the Black Female Union Band Society Cemetery from the predominantly White Oak Hill Cemetery (the numerous gravestones and monuments present on the hillside visible through the trees on your left).

"Thousands of people are buried in these cemeteries, but I do not see many gravestones. Why is that?"

Research has identified 592 surviving grave and monument stone artifacts. While this figure omits many undocumented memorials for persons interred on the cemetery hillsides, stone artifacts that have sunk or become buried under vegetation, and those removed from the grounds by families or thieves, it bears no correlation to the thousands of recorded burials in the two cemeteries. For example, Mount Zion Methodist Church death records for1863-1931 identify 2,769 persons as buried in the Mount Zion Cemetery, and 6,313 burials are recorded in 1880-1930 death records of the Health Office of the District of Columbia (the Health Office figure is commonly accepted as a combination of burials in both cemeteries).

For the past year, a dedicated team has been working to consolidate previous research and new sources of death, burial, and biographical information for persons interred in the cemeteries into a single database. The effort has resulted in a database of 4,300 records containing known birth, family relationships, addresses, occupations, enslavement, military service, death, and burial information. Portraits, grave/memorial, death and funeral press notices, and key personal document images are being collected as well.

While efforts to discover the identity of additional persons buried in the cemeteries and add to the biographical information and supporting documentation for already known persons continue, the Foundation has created a first-ever "Cemeteries Information System" that enables descendants, researchers, and the public to easily access, search, and reveal biographical Profiles for persons of interest.

Gravestones provide both insight and incomplete accounting of the interred

Burial plots for enslaved, paupers, and transients may not have had formal markers at all; their graves may have been honored with ballast stones, flowers, or saplings. Another memorial tradition, perhaps connecting life with the after-life, was to adorn graves with articles enjoyed or meaningful to the life of the deceased - such as a hobby horse, a wheelbarrow, or a high chair. Given the early 1800’s origin of the oldest burial areas of the two cemeteries, grave markers for many of the earliest interred working-class whites, enslaved or freed blacks were made of easily sourced and inexpensive wood, sandstone, or concrete, with details about the deceased painted or lightly inscribed on the artifact. While a few surviving wood markers are held at Mount Zion United Methodist Church, and remnants of some early concrete and sandstone markers still exist on the grounds, many early markers have been consumed over time by the forces of nature. Some of the older surviving stone artifacts you will encounter were fashioned from more durable and expensive Virginia 'blue stone'.

As you approach the tall Logan monument, look for the white marble gravestone of Louis Cartwright. The ‘chain links’ carving at the top of the headstone is sometimes misinterpreted as the deceased having been enslaved. In fact, the links represent "Friendship, Love, and Truth" and denote membership in the “Grand United Order of Odd Fellows”, a black men's mutual aid society founded in the U.S. in 1843.

Louis, born in 1817 (or 1818) and died on March 4, 1875, was enslaved by Presly and Mary Saunders until purchased by his father, the Reverend Joseph Cartwright, Sr. on April 17th, 1837 for $600. The Rev. Cartwright, one of the first Black pastors of Mount Zion United Methodist Church, also purchased his enslaved wife Susanna, son Joseph Jr, and daughter Norah Cartwright (Brown) from their respective owners. The Reverend manumitted (freed) his three children, with their manumission legally recorded September 23, 1839.

Louis's life was transformed once freed. The U.S. Census of 1860 lists Louis [Lewis], aged 43, as a laborer owning real property valued at $800. Church records and City Directories inform us that he was a Sexton at Mount Zion Methodist Church, a grocer, and resident at 41 West Street (present-day P Street NW).

Within the Logan family burial plot lies the granite memorial to Franklin Jennings and his wife Mary Logan Jennings.

Franklin Jennings was born enslaved to enslaved Fanny Gordon (enslaver Charles P. Howard) and enslaved Paul Jennings (enslaver James Madison, future U.S. President) on the Howard estates in Orange, VA. Franklin was manumitted in 1856. At age 26, he traveled to Washington, DC, where on May 12, 1864, he enlisted as a Private in the U.S. Army, assigned to the 5th Regiment, Massachusetts Colored Cavalry (see Franklin's enlistment document). His Civil War military assignments included guarding Confederate prisoners, participating in the battle of Petersburg, VA, and being one of the first U.S. Army regiments to enter and capture the Confederate capital, Richmond, VA. Franklin survived the war, became a farmer, married Mary Logan (Mary, a past President and Trustee of the Female Union Band Society was the last person to be buried in either cemetery), became a notable landowner, and raised a large family.

The cemeteries are the resting place for a number of Black persons who served in the U.S. Army, Colored Troops, White and Black persons who served in militias or regular armed forces of the United States, and persons who registered for military service. Click to access the Cemeteries Information System, check the "Military Service" box, and SEARCH to view persons with military service affiliation

Franklin Jennings (1836-1926) and his and his wife Mary Logan Jennings (1850-1950)

Rev. Joseph Cartwright, was born into slavery on July 15, 1783 in Maryland. He was manumitted by enslaver John Rose in 1819.

He traveled extensively - traveling as far as Salem Massachusetts where he worked with abolitionist Charles Turner Torrey. He also traveled in Fairfax, Loudoun and Prince William Counties, preaching and raising money to free family members and other enslaved persons. He was one of the first Black preachers to be recognized by the Baltimore District of the Methodist Conference, and given a salary.

During his life he purchased the freedom of his children Alfred, Lewis, Joseph Jr, and Nora - and the freedom of his wife Susanna.

He died on December 2, 1851, aged 68, in Washington, District of Columbia. He was buried on December 4, 1851 in the Female Union Band Society Cemetery.

Reverend Joseph Cartwright, Sr.and Susanna's memorial - a bluestone slab vault top, located on the hillcrest behind the Logan family plot

Though little is known about Nannie, a child buried in the grounds (May 26, 1848 - May 18, 1856), her gravestone creates a connection with many visitors. It is not uncommon to find birthday cards, ribbons, toys, and other mementos left in her honor.

Nannie memorial - bluestone slab headstone (no base), with a crown carved in the style frequently found in the Old Methodist Burying Ground, is located immediately behind the Logan plot.

Volunteers, enabled by generous donations, perform restorative cleaning, mending, and remounting of gravestones such as Matilda Cartwright’s, daughter of freed slave, Louis Cartwright.

The images below are the results of ‘ground-penetrating radar’ and ‘magnetic gradiometer’ scans of unobstructed areas of the plateau area of the two cemeteries. The scans depict significant disturbance of soil throughout the property, as well as the presence of numerous metal objects as would be expected in a burial ground (coffin nails, handles, and hinges). The results confirm written and oral records of the two cemeteries: the park-like plateau and hillsides are, in fact, the sacred final resting place for thousands of deceased persons.

Our next stop is the cemetery vault

Look for the "Cemetery Vault" sign located at the wood's edge along the hillcrest of the memorial park. Carefully walk down the stairs adjacent to the sign and you will arrive at the entrance of the vault.

If the door is closed, feel free to open it (some strength is required as the door is heavy)

The vault was used to hold remains of deceased persons until their burial plots had been prepared (delays due to inclement weather or when the burial ground was too frozen to be opened). Although having been repaired at different times, the vault is believed to have existed since the early 1800s.

The vault, and the cemetery grounds more generally, are believed to have served as a waypoint for enslaved persons making their way to freedom on the Underground Railway. With guidance, sustenance, and supplies received from sympathetic persons in the nearby community, freedom seekers could travel north along Rock Creek, through Maryland, to relative freedom in Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania was attractive to freedom-seeking Black people given the State's 1780 adoption of ‘gradual abolition of slavery’ laws, and the population being generally indifferent to enforcing the federal Fugitive Slave Act which required repatriation of runaway slaves. Pennsylvania’s abolitionist position strengthened in 1820 with the passage of personal liberty laws which imposed fines and jail sentences for kidnappers of suspected fugitives, and required judges to file reports any time they deemed someone a fugitive and returned him or her to slavery.

Before leaving the vault area, scan the wooded hillside from far left to far right - while steep, this land is known to be the burial place for many persons. If you walk about the hillside you may encounter burial plot markers, headstones, and other artifacts (most covered with vegetation, and some large gravestones shifted downhill by the force of gravity).

Proceed toward the large Doughty family obelisk located in the Mount Zion Cemetery

The large obelisk-topped monument honors the Doughty family - early members of the Montgomery Street Methodist Church. William Doughty (1772 - August 19, 1859) was a master shipbuilder. In 1812 he built the 363-ton capacity sailing ship "General Lingan" for Georgetown merchants Washington Bowie and John Kurtz. William, his wife Sarah, and a number of their children and relatives are buried near the monument.

As you approach the tall obelisk, take a moment to stop and visit the collection of graves and gravestones on your left.

Some of the memorials in this grouping were placed here for safekeeping while the grounds of the two cemeteries experienced significant restoration required after being untended for several decades. Where sufficient historical documentation exists, it is intended that memorials will be returned to their original grave locations.

Grave markers, memorials, and grave plots reveal history - Memorial material selection, design, and inscription techniques provide useful indicators of the era of burial as well as the social status and relative wealth of the deceased (or the persons paying for the burial). Many individuals buried in the cemeteries, given their enslaved or working-class economic status, were honored with wood, sandstone, or concrete memorials. The details of the deceased would be hand-carved, traced in wet cement, or painted on the marker. These memorials often reflect the fact they were crafted by family members or a friend rather than a professional monument tradesman.

Some of the oldest and more elegantly crafted artifacts which remain were fashioned from the more expensive 'bluestone' sourced from Virginia. These take the form of large rectangular slabs topping in-ground vaults, and arched crown slab gravestones that would be buried 18 to 24 inches into the ground (headstones mounted on a stone base were a design fashion that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century). As the means to transport raw materials within the colonies expanded, together with the increased wealth of an expanding middle class, the use of heavier and more expensive to quarry and carve, marble and granite stones became popular. Large family memorials (such as the Logan, Baker, and Doughty edifices) as well as burial plots enclosed with iron fencing, 'gas pipe' or stone boundaries are another likely indication of wealth and elevated social status of the deceased or their family. You will find larger, more modern-looking headstones with older decedent birth and death dates. These memorials were likely gifts from descendants erected many years after the passing of the honored individual.

The Old Methodist Burying Ground is the oldest truly biracial burying area remaining within the District of Columbia and the only cemetery of that distinction located in Georgetown.

Adjoining the Doughty monument is the "Old Methodist Burying Ground" - the first formal cemetery established on the property

Although the two burial grounds are often characterized as being ‘Black cemeteries’, in truth, the original Old Methodist Burying Ground is the final resting place for White community leaders and working-class persons of European ancestry, enslaved Africans and their enslaved descendants, freed and free Blacks, and persons with Native American ancestry.

Present-day Mount Zion Cemetery exists as the result of several property use agreements and changes in ownership, as well as the founding of the Mount Zion Church itself. The original Old Methodist Burying Ground property was acquired by Ebenezer Eliason from Thomas Beall in 1808 on behalf of Montgomery Street Methodist Church (Inscriptions on gravestones in the grounds indicate burials were taking place as early as 1804 before the acquisition was formalized). Burial plots were sold to recoup the purchase price of the grounds. Of the 358 burial spaces noted in the original land transfer survey, 265 were designated for White church members and 93 for (predominantly) enslaved Blacks. 209 White and 39 Black plots sold quickly (an additional four held aside for church pastors). The burying ground is approximately one-half mile from the location of the Montgomery Street Meeting House which was located on historic Montgomery Street (today's 28th Street NW) between Bridge (M Street NW) and Olive Streets.

The Montogomery Methodist Church's inclusion of enslaved persons in church services expanded to include freed and free Black persons. In a short time, Black people comprised nearly half of the church membership. Dissatisfied with segregation policies and practices of the Church, desirous to have their own pastors, and a church that more meaningfully reflected the Black community, in 1816, 125 Black members left to establish their own church - Mount Zion United Methodist Church.

Meanwhile, in 1822 Montgomery Street Methodist Church acquired additional land which approximately doubled the original size of the burial ground. The expanded cemetery continued to host segregated burials with plots selling for $15. The burial ground became “Mount Zion Cemetery” in 1879 when the Montgomery Street Methodist Church, now reformed as Dumbarton United Methodist Church, leased the property to Mount Zion Church for 99 years. Not all Dumbarton church members supported the lease agreement, and as a result, some had deceased family members disinterred and reburied in the new nearby Oak Hill Cemetery. The Mount Zion Church's assumption of the lease and the disinterment of White remains contributed to the cemetery becoming identified as "the colored cemetery" - the burial place for Georgetown’s growing Black community. In 1978, the lease ended, and legal control of the property reverted to Dumbarton United Methodist Church. By Special Warranty Deed, on Feb. 9, 2017, Dumbarton United Methodist Church transferred all right, title, and interest in the cemetery to the Mount Zion Church.

Cast concrete memorial for an unknown decedent with an unidentified inscribed symbol. The memorial is located in the Old Methodist Burying Ground of the Mount Zion Cemetery

Acquiring a higher quality, yet affordable, gravestone

It was not uncommon for working-class families or friends to purchase and 'repurpose' a finished marble or bluestone memorial originally marking a veteran's grave in a military cemetery as an affordable, more appealing, and durable alternative to wood, sandstone, or cast concrete memorials for a loved one. This option came about when US military cemeteries chose to replace large numbers of headstones of various designs and materials originally placed at veteran graves by families and friends with a “standard” grave marker (like those seen today in Arlington and other national cemeteries). The original headstones were sold off as stone "surplus" to monument companies and builders.

The memorial for Julia Johnson (1863-1812), located reclined near the Doughty obelisk, is an example of a reworked military headstone. Her marker was once the headstone for the Arlington Cemetery grave of Chief Engineer J.D. Robie, United States Navy. His burial stone was replaced at some point with a new military standard headstone, and the orphan stone was acquired and prepared for reuse by a stonemason. The limited funding favoring the decision to reuse a discarded stone also influenced the new design. Julia's inscription details and shaping of the crown top show less stone carving finesse than found on more expensive expertly carved memorials.

In the transformation the surplus headstone is inverted 'top becomes bottom’, turned over, and the new inscription carved on the new 'top' of the stone blank (When installed upright, the veteran's details are hidden in the ground).

Impact of the Global Spanish Flu Epidemic

You may have noted a number of gravestones with death years of 1918-1920, and many of those being younger persons. Headstone inscriptions, Mount Zion Church death records, and Health Office of the District of Columbia death and burial records give testimony to how flu death disproportionately affected Georgetown's Black community - particularly younger individuals. The global flu pandemic broke out near the end of World War I. In the United States, the illness was first identified in returning military personnel in the spring of 1918. By the fall of 1918, Washington, packed with federal war workers and military servicemen, had become one of the most affected U.S. cities. The first case in Georgetown was identified on September 26, 1918. By the end of the epidemic, 33,719 District residents had fallen ill, and 2,895 residents had died. The Report of the Health Office of the District of Columbia recorded 437 and 304 burials of persons in the Mount Zion and Female Union Band Society cemeteries, respectively, in the epidemic years of 1918 and 1919. The death counts, approximately double the average of other years, are attributed to the epidemic. Or, as noted at the beginning of the tour, in these cemeteries "Death Reflects Life."

This concludes the guided tour. We hope your visit created new personal awareness and a thirst to continue your education.

To fully value the cemeteries and the thousands of individuals buried within their grounds, it is necessary to understand the history of the cemeteries AND the lives and contributions of the enslaved Africans, their enslaved descendants, and freed Black persons to the establishment of Georgetown from its earliest days as a frontier port to the present, and to the transition of the United States to a post-slavery era.

The Mount Zion-Female Union Band Historic Memorial Park Foundation website offers many useful information resources to assist you in your journey:

-

Recent media coverage and collaborative education outreach programs

-

Publisher information for "Black Georgetown Remembered", and "Escape on the Pearl"

And please take a moment to learn how you can become involved in our many ongoing volunteer activities, or make a financial contribution to support our preservation and restoration efforts